Introduction

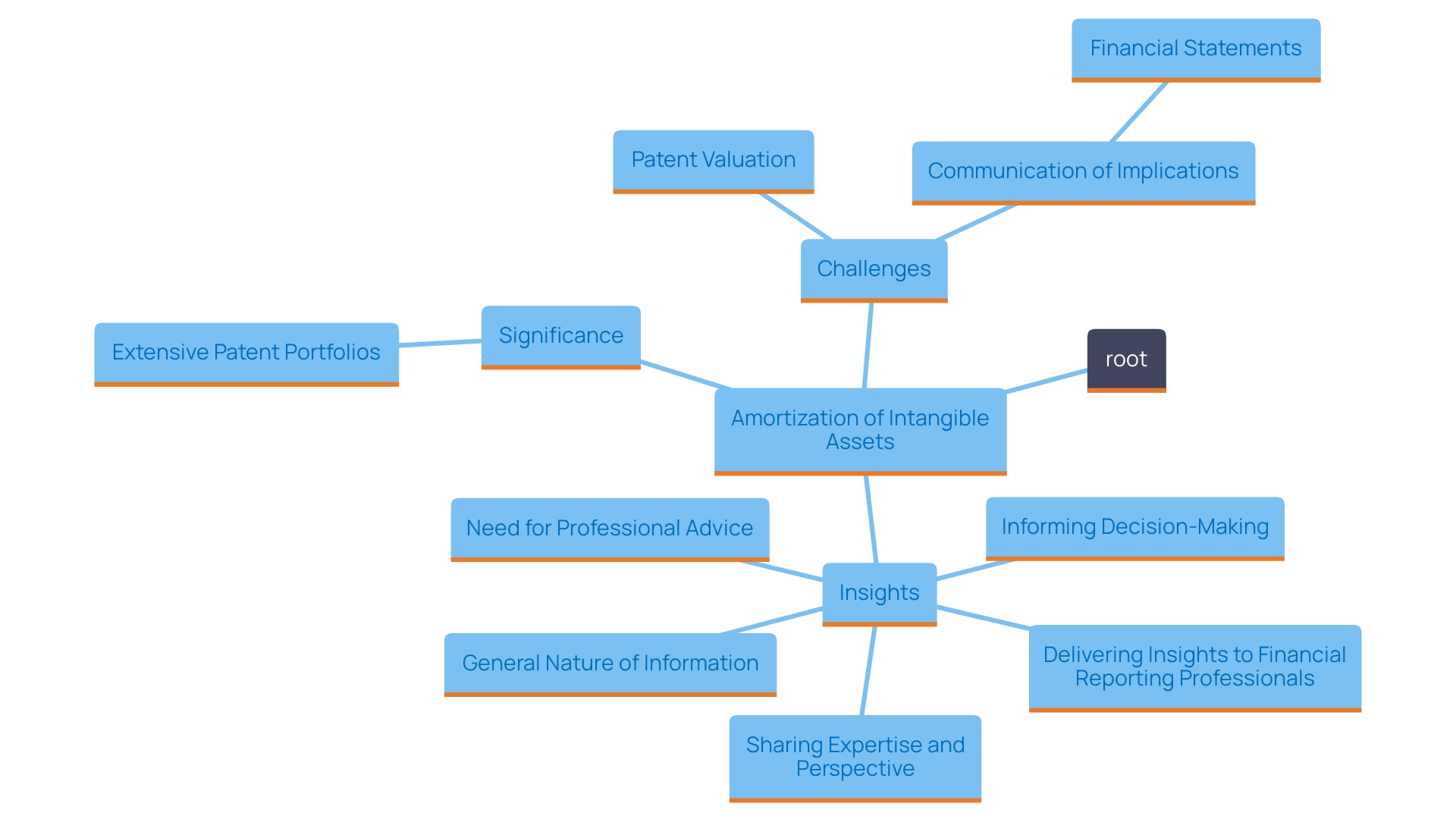

Understanding amortization is crucial for navigating the complexities of financial reporting, particularly regarding intangible assets. This accounting process systematically allocates the cost of assets such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights over their useful lives, ensuring that financial statements accurately reflect their diminishing value. The implications of effective amortization extend beyond mere compliance; they play a pivotal role in strategic decision-making, cash flow management, and investment planning.

As organizations increasingly adapt their financial strategies to a dynamic market landscape, grasping the nuances of amortization methods, calculations, and their impact on financial health becomes imperative for CFOs. This article delves into the intricacies of amortization, offering insight into its types, calculation methods, and the vital differences between amortization and depreciation, while also highlighting examples and the benefits and limitations of this essential accounting practice.

What is Amortization?

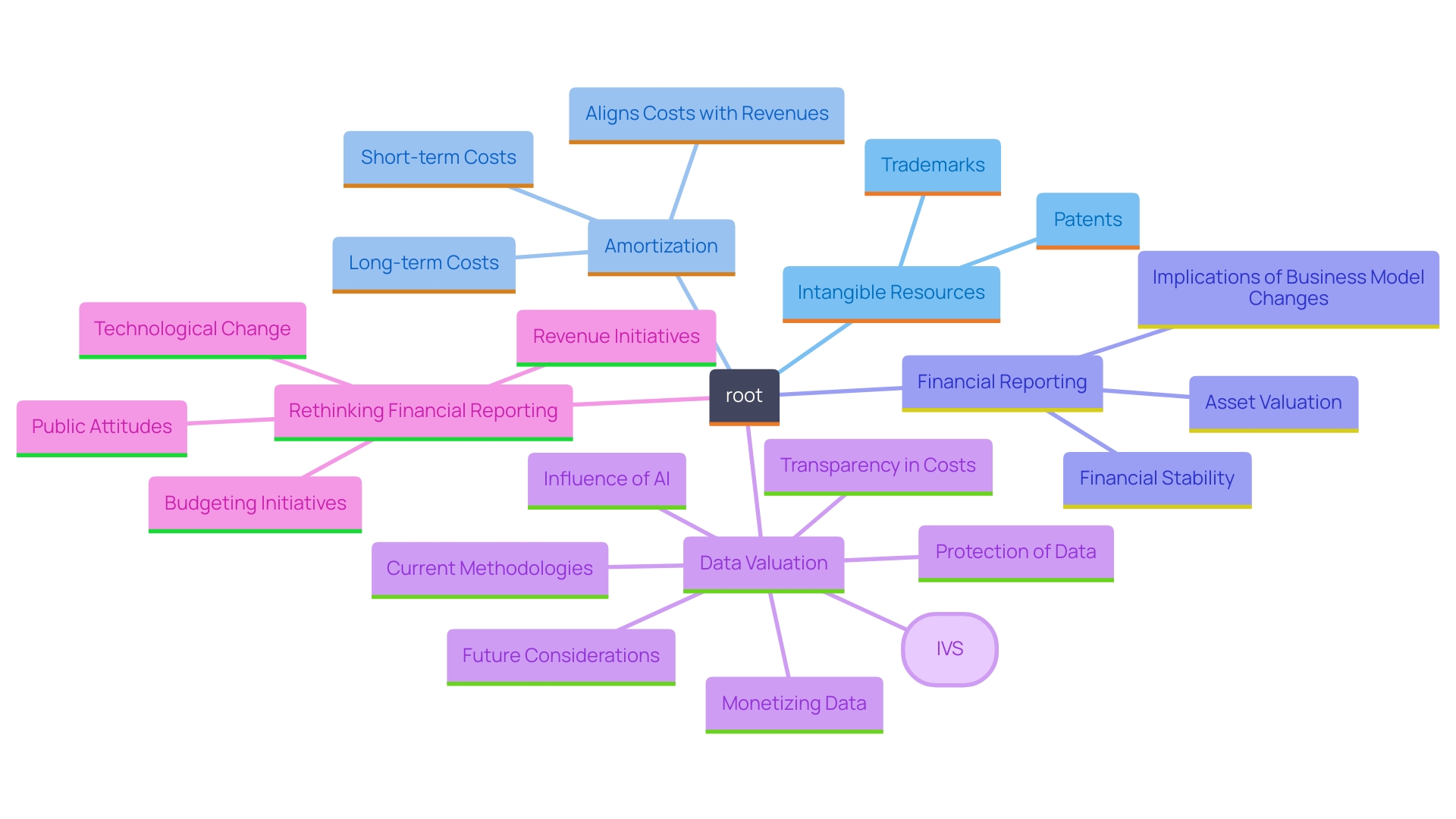

Amortization is a key accounting process that systematically decreases the recorded value of intangible resources over a designated period. This process enables organizations to distribute the initial expense of a resource throughout its useful life, thereby demonstrating its gradual usage or decline in value. Commonly, amortization is applied to intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

For instance, consider the complexities involved in analyzing patents. Financial professionals often face challenges when assessing the value of patents, which necessitates a deep understanding of their claims and the technology involved. This is especially accurate in instances of patent disputes, where the interaction of multiple elements—such as claim interpretation and the amount of prior art—can render the evaluation complex. As pointed out by industry specialists, "the materiality refers to the significance of the expense item in the context of the accounting statements."

Moreover, companies like Qualcomm, with a robust patent portfolio exceeding 140,000 global patents, exemplify the economic implications of amortizing intangible assets. 'Their strategy intertwining patent licensing with product sales underscores how cost allocation impacts cash flow and revenue recognition in innovative sectors.'.

'In the economic environment, it is crucial to effectively communicate the implications of amortization.'. This involves translating complex figures into relatable narratives, ensuring stakeholders grasp the significance of these intangible resources. As economic communication evolves, professionals are increasingly leveraging visuals and straightforward metrics to enhance understanding and engagement, thereby improving decision-making in budgeting and resource planning.

Types of Amortization

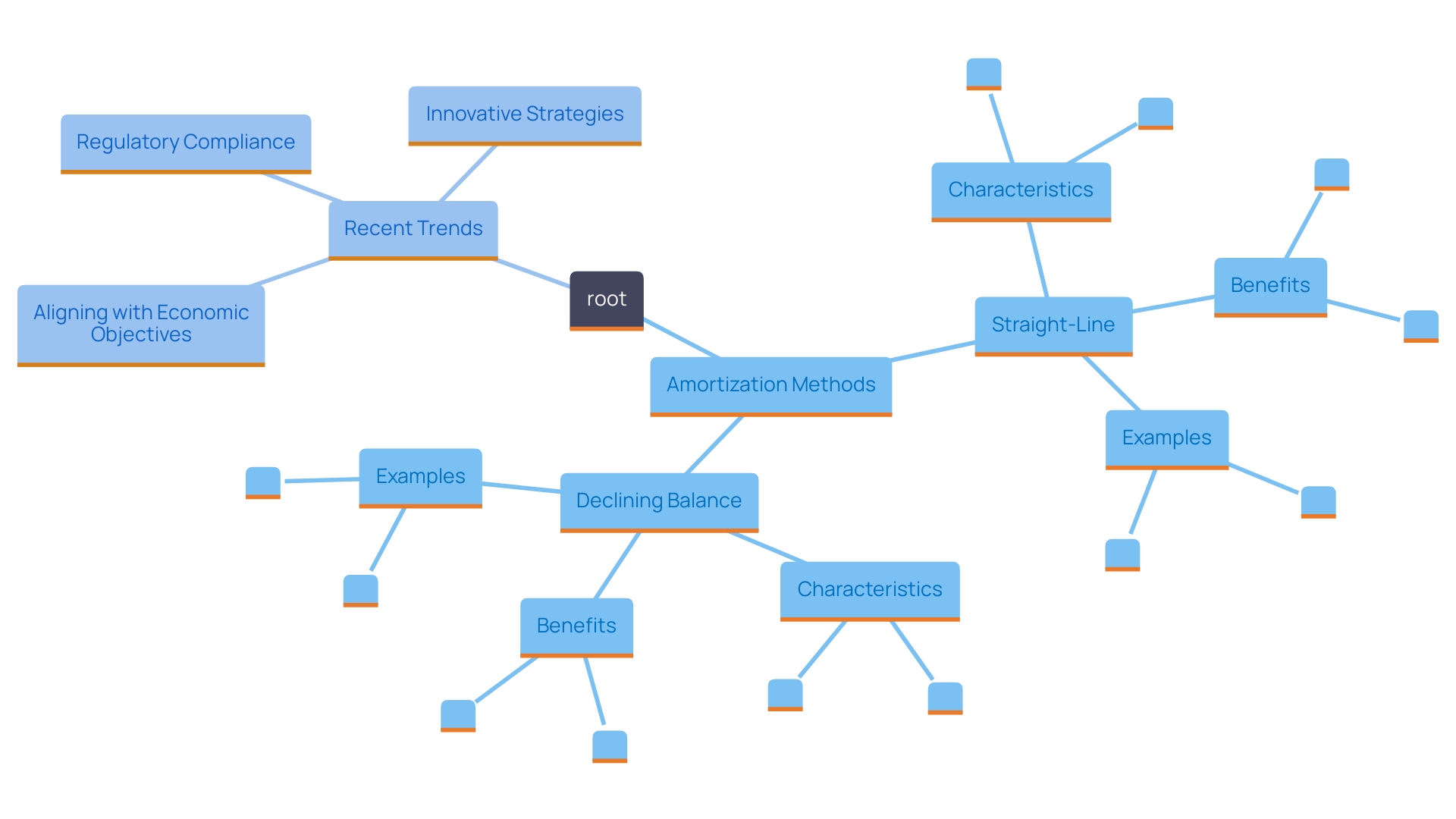

Amortization is a vital accounting principle employed to distribute the expense of an intangible resource over its useful life. Two primary methods of amortization are the straight-line method and the declining balance method, each serving different economic strategies and implications.

The straight-line method is the most straightforward approach, distributing the total cost of the resource evenly across its useful life. This leads to consistent cost recognition each period, which simplifies budgeting and financial forecasting. For instance, if a company obtains an intangible resource for $100,000 with a useful life of 10 years, it would acknowledge an annual amortization cost of $10,000. This predictability can be particularly beneficial for organizations aiming to maintain steady cash flow and liquidity.

In contrast, the declining balance method speeds up recognition of costs, allowing businesses to record higher deductions in the earlier years of the item's lifespan. This is especially beneficial for companies that foresee swift fluctuations in their resource values or wish to enhance their tax situations early on. Using this approach, an asset first assessed at $100,000 with a depreciation rate of 20% would lead to an expense of $20,000 in the first year, then $16,000 in the second year, and so on. This approach can be attractive for entities that face significant initial costs and benefit from immediate tax relief.

Recent trends indicate that businesses are increasingly adjusting their depreciation strategies to reflect changes in operational circumstances. For instance, a bank recently shifted the management of a sub-portfolio of private corporate bonds from a model focusing on selling to one aimed at holding for collection. This transition necessitated a reclassification of these bonds into the amortized cost category, thereby removing prior losses from equity and adjusting their fair value. Such strategic shifts underscore the importance of aligning amortization methods with broader economic objectives and regulatory compliance.

Grasping these techniques not only supports precise monetary reporting but also guides investment choices and risk management approaches, especially in variable economic conditions.

Amortization of Intangible Assets

Non-physical resources, including patents, trademarks, and goodwill, do not have a tangible form, but they are vital to a company's economic well-being. Amortization is the process that aligns the cost of these intangible assets with the revenue they generate over time, ensuring a more accurate reflection of economic performance. 'This matching principle is essential for clear monetary reporting and compliance with accounting standards, which mandate that costs be acknowledged in the same timeframe as the revenues they assist in producing.'.

Grasping the significance of depreciation is essential for efficient resource management. For instance, the importance of an amortization cost can vary widely based on its duration and the asset's value. 'In the context of monetary reports, differentiating between long-term and short-term costs can inform strategic choices on resource distribution and fiscal planning.'. The choice between recording an expense directly to the profit and loss statement (PNL) or initially placing it on the balance sheet can significantly influence a company's economic picture.

Recent changes in business models, such as a bank's shift from managing private corporate bonds as "held to collect and sell" to "held to collect," underscore the importance of reevaluating intangible asset valuations. 'This reclassification enabled the bank to eliminate significant net losses from its equity, illustrating how strategic choices regarding expense allocation can influence overall financial stability.'. Such insights highlight the necessity for CFOs to stay alert in modifying their depreciation strategies in response to changing market conditions.

How to Calculate Amortization Expense

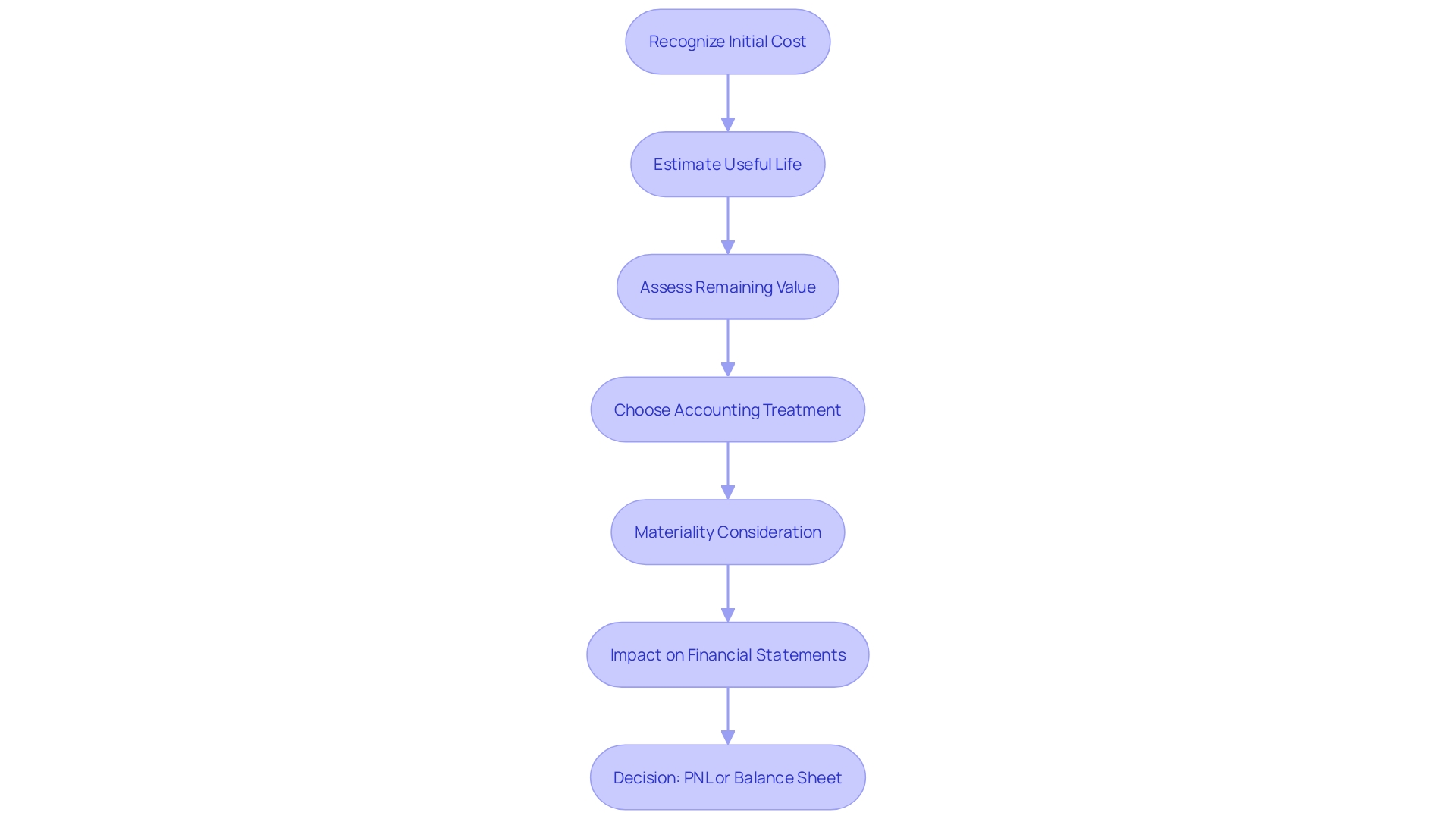

Determining the expense related to the gradual reduction of value includes several important stages: recognizing the initial cost of the intangible resource, estimating its useful life, and assessing any remaining value. The most prevalent technique employed is the straight-line repayment method, which streamlines the process and offers clear monetary reporting.

The formula for straight-line amortization is represented as:

( ext{Amortization Expense} = \frac{\text{Cost} - \text{Residual Value}}{\text{Useful Life}})

This method allocates the cost of the intangible asset evenly over its useful life, making it easier for CFOs to manage financial statements. Grasping the relevance of these costs is essential; the importance of the depreciation charge can fluctuate depending on the asset's life span and its effect on the financial reports. For instance, an item with a longer useful life may have a different amortization approach compared to one with a shorter life.

When considering which expenses to classify directly to the Profit and Loss (PNL) statement or initially to the Balance Sheet, companies often face the decision of how to best reflect these costs in their accounting practices. 'This consideration can significantly affect cash flow management and adherence to reporting standards, leading to strategic decisions that align with long-term monetary goals.'. 'The recent shift by a bank to change its business model in managing private corporate bonds illustrates how such decisions can reclassify assets and affect overall economic health.'. The bank transferred its bonds from "held to collect and sell" to "held to collect," emphasizing the significance of adjusting monetary strategies in response to changing market conditions.

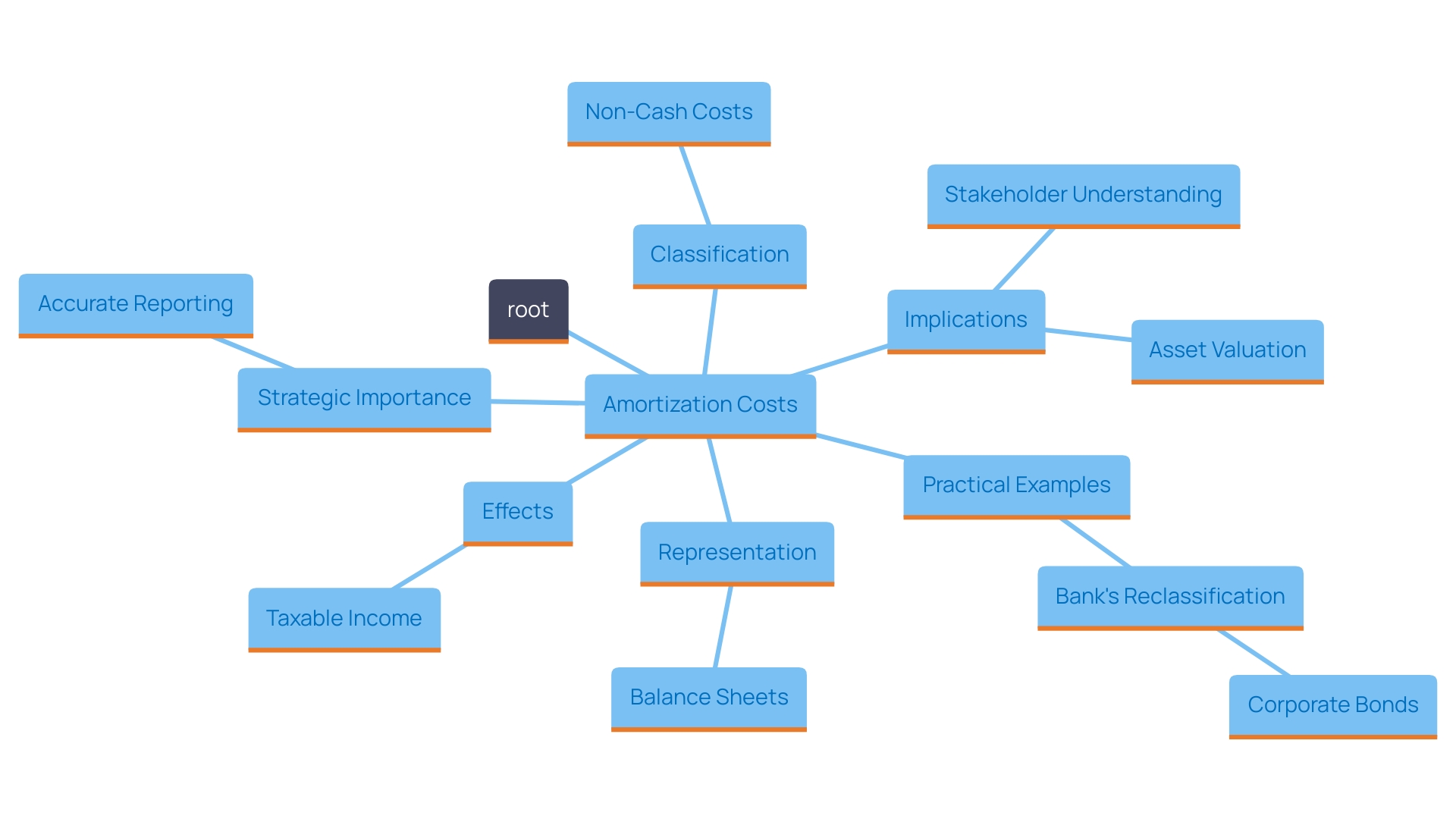

Recording Amortization Expenses

Amortization costs play a crucial role in financial reporting, classified as non-cash costs on the income statement. This classification effectively reduces taxable income, allowing organizations to optimize their tax liabilities. Furthermore, these costs are shown on the balance sheet, where they reduce the carrying value of intangible resources, such as patents or trademarks, throughout their useful lives. This systematic reduction provides a clear picture of asset valuation, aligning it with the actual economic reality of the company’s operations.

Precise documentation of amortization is essential for presenting an honest economic position. Misrepresentations can lead to significant misunderstandings among stakeholders regarding the company's monetary health. As noted in industry insights, "the materiality refers to the significance of the expense item in the context of the statements," highlighting the importance of precise reporting.

In practical terms, consider a bank that recently shifted its business model for a portfolio of private corporate bonds. By reclassifying these bonds from a fair value measurement to an amortized cost category, the bank effectively removed material net losses from its equity, stabilizing its fiscal outlook. This situation highlights how tactical choices regarding debt repayment can directly impact a company's equity and overall economic stability.

As organizations strive for transparency and accuracy, understanding the implications of amortization expenses becomes not merely an accounting exercise but a strategic imperative that can significantly impact planning and risk management.

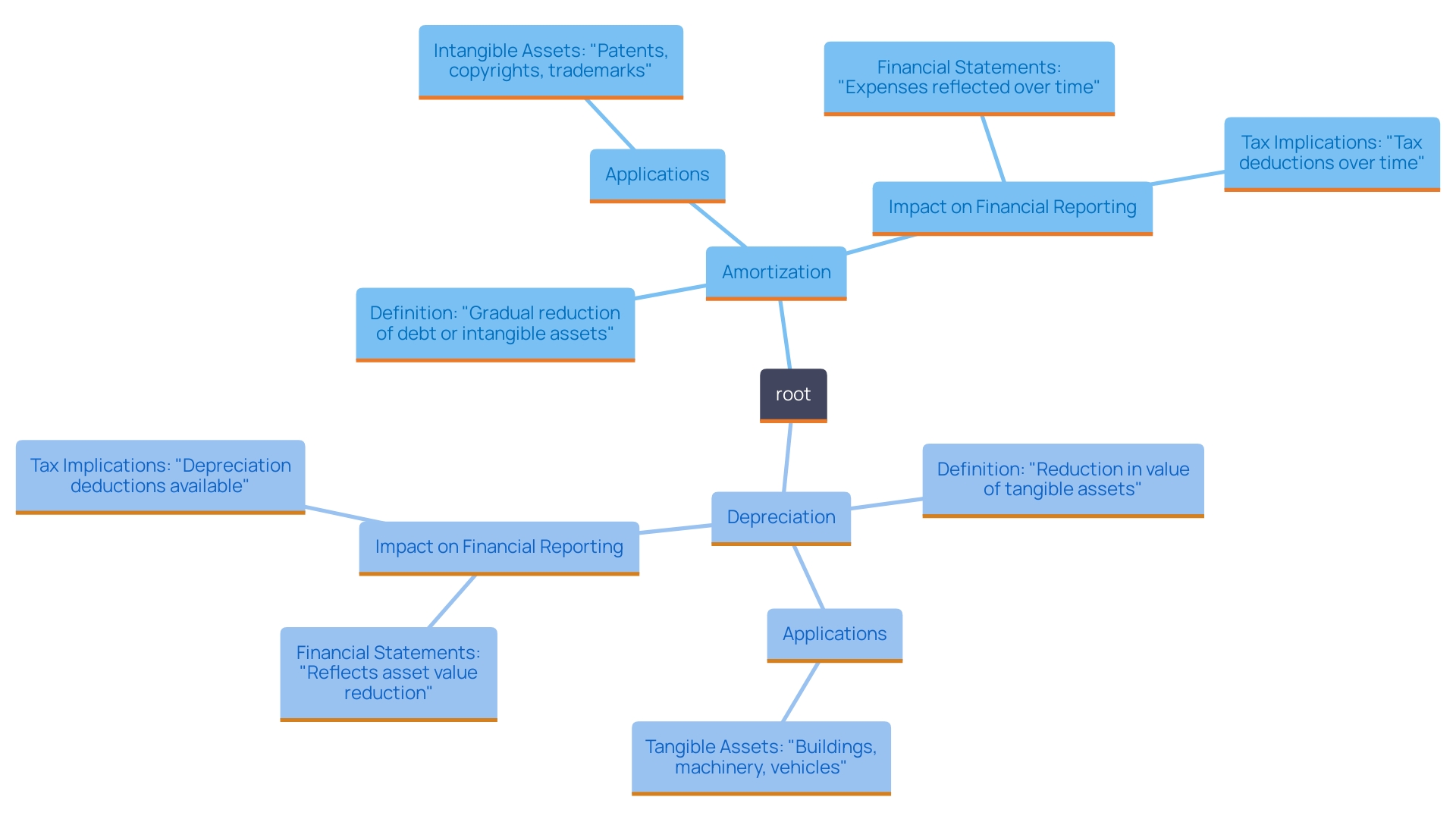

Difference Between Amortization and Depreciation

Amortization and depreciation are both essential financial concepts used to allocate the cost of a resource over its useful life, yet they apply to distinct types of resources. Amortization is specifically utilized for intangible resources—such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights—allowing businesses to spread out the initial costs over the resource's expected life. This practice not only conforms to accounting principles but also helps in precisely representing the value of the item on the balance sheet.

Conversely, depreciation is used for physical properties, such as machinery, vehicles, and buildings. It accounts for wear and tear and the gradual decrease in value of these physical assets over time. For instance, a manufacturing company may use depreciation to account for the decline in value of its equipment as it ages and is utilized in production.

The difference between amortization and depreciation is essential for accounting reporting and analysis, particularly in the context of materiality. In monetary reports, the importance of these cost items can influence the overall view of an organization's economic well-being. For example, a company must decide whether to record an expense directly to the profit and loss (PNL) statement or initially place it on the balance sheet, influencing both current and future fiscal statements.

This selection frequently depends on the resource's lifecycle and its significant effect on monetary reporting. Comprehending these differences guarantees that organizations can handle their accounting practices efficiently, offering a precise and transparent perspective of their economic position.

Examples of Amortization

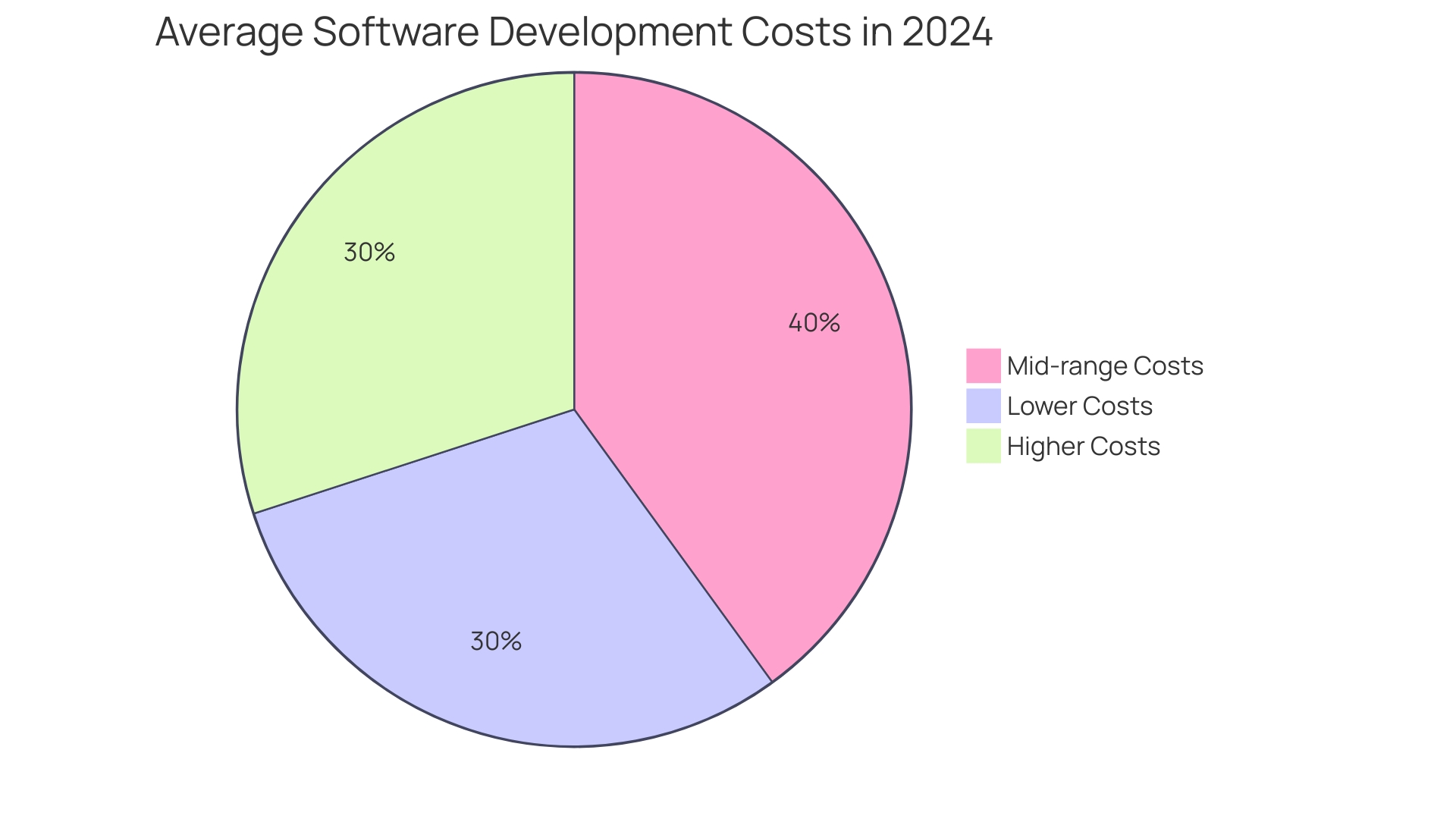

Amortization costs are a crucial component in financial statements, especially for intangible resources like software licenses, patents, and trademarks. For instance, consider a patent purchased for $120,000 with a useful life of 10 years. Under the straight-line amortization method, this would lead to an annual amortization cost of $12,000. This consistent expense recognition helps organizations align their reported profits with the consumption of these assets over time.

In the context of software development, understanding how to categorize these costs is essential for accurate financial planning. In 2024, the average cost of software development ranges from $70,000 to $250,000, influenced by various factors including project specifics and market conditions. Companies that can effectively capitalize on their software investments—through innovative features that drive revenue—often see a more favorable return.

Moreover, the implications of spreading costs extend beyond mere compliance with accounting standards. For companies operating in competitive markets, such as software, maintaining a clear grasp on amortization can offer insights into overall market positioning and strategic advantage. Companies showcasing creativity and flexibility often receive greater recognition, emphasizing the significance of precisely representing these intangible resource costs on the income statement.

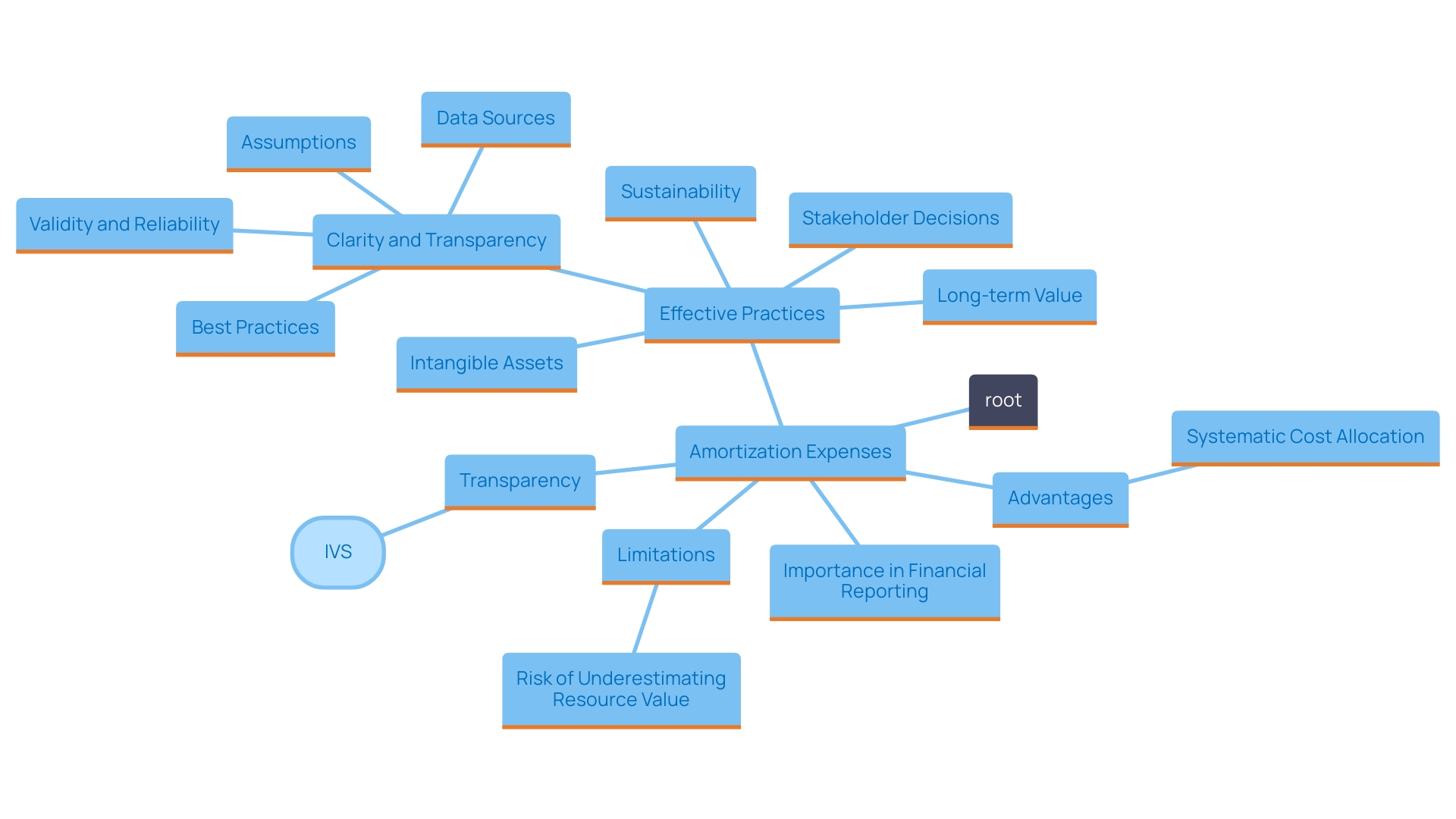

Benefits and Limitations of Amortization

Amortization expenses serve a crucial role in the financial reporting of intangible resources, offering a structured approach to cost allocation that enhances accuracy and transparency in financial statements. By systematically spreading the cost of a non-physical resource over its useful life, companies can better reflect the resource's contribution to revenue generation in their income statements.

Despite these advantages, there are notable limitations associated with amortization. One significant concern is the risk of underestimating the true worth of a resource. For instance, the method relies heavily on estimates regarding the useful life and residual value of the resource, which can be inherently subjective and complex. This complexity can lead to discrepancies between recorded values and the actual economic conditions of the resource, potentially misleading stakeholders regarding the organization’s monetary well-being.

Moreover, the recent changes in valuation practices emphasize the necessity for transparency. The framework outlined in the International Valuation Standards (IVS) emphasizes the significance of properly revealing the expenses related to data and intangible resources. This organized investigation seeks to assist specialists in maneuvering through the assessment terrain, guaranteeing that the economic importance of non-physical resources is precisely represented in accounting reports.

As organizations increasingly recognize the importance of intangible assets, effective amortization practices become essential. The need for accurate financial reporting, particularly in an environment influenced by artificial intelligence and evolving market dynamics, underscores the importance of continuously refining these practices to align with current methodologies and future considerations.

Conclusion

Understanding amortization is an essential aspect of financial reporting, particularly for intangible assets. This accounting process not only enables organizations to allocate costs over an asset's useful life but also ensures that financial statements reflect the true value of these assets. The implications of effective amortization strategies extend to cash flow management, strategic decision-making, and compliance with accounting standards, making it a critical focus for CFOs.

Various methods of amortization, such as the straight-line and declining balance approaches, cater to different financial strategies and operational needs. Each method's selection can significantly influence an organization’s financial reporting, tax liabilities, and overall financial health. Recent trends highlight the necessity for businesses to adapt their amortization practices in response to changing market conditions, ensuring alignment with broader financial objectives.

Moreover, the distinction between amortization and depreciation is vital for accurate financial reporting. Understanding these differences helps organizations manage their accounting practices effectively, providing a transparent view of their financial positions. While amortization offers significant benefits, such as enhanced accuracy in financial reporting, it also comes with limitations that necessitate careful consideration and strategic adjustments.

In summary, a comprehensive grasp of amortization's intricacies is imperative for CFOs aiming to navigate the complexities of financial management. By refining amortization practices and aligning them with organizational goals, businesses can enhance their financial strategies and improve overall stability in a dynamic economic landscape.